In the opening scenes of the film Concussion --in theaters today--women in sports bras pedal furiously on stationary bikes as the camera shifts in and out of focus. Wheels spin, and images of large suburban homes flicker on the screen before cutting to the character of Abby Abelman (Robin Weigert), a lesbian housewife in her 40s who is first seen clutching a bleeding forehead.

The word “concussion” is defined as a temporary unconsciousness caused by the blow to the head. But, as Weigert points out, there’s more to the word than just a medical sense.

“There’s a meaning for the word ‘concussion’ that isn’t literal, which is just a jolting event, “ Weigert says, clapping her hands together loudly for emphasis. “It is a literal version of something that could happen in a non-literal way.”

Concussion—a film about a woman who, starved of intimacy in her New Jersey household, embarks on a secret life as Eleanor, an escort in Manhattan—has become its own jolting event in the world of cinema. Directed by first-time director and screenwriter Stacie Passon and produced by Rose Troche of Go Fish fame, the film has already earned accolades, including a Teddy Award at the 2013 Berlin International Film Festival as well as admission into this year’s Sundance. It opens Friday in theaters and on demand, its own accomplishment for a film that explores LGBT themes and characters.

Critics have hailed it as the lesbian Belle de Jour, a seminal French film about a housewife, played by Catherine Deneuve, who also embarks on a fantasy of prostitution. But the comparison between these two characters is not precise, says Weigert.

“An artist without an art form,” is how Weigert would more appropriately describe Abby Abelman before the blow. In Weigert’s view, sex for Abby becomes its own art form, “one that she refines over the course of the film. She learns more and more about it.”

Tall with looks that are also striking, Weigert, known for her past roles as Calamity Jane in HBO’s Deadwood and Hannerole in The Good German, sits in the center of a large white room within a Beverly Hills hotel. The setting echoes the milieu of a light-filled Manhattan room, where her Concussion character, jolted into a sexual awakening after a blow to her head, meets women who pay her for sex.

“Sexuality and creativity are very linked, I think,” she says. “And so the fact that this woman finds expression sexually almost feels like a metaphor… for self-expression, period.”

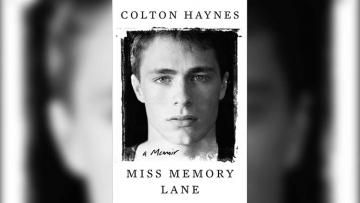

Weigert as Abby

To prepare for her character, Weigert says she restricted her diet to 1,400 calories per day, limiting her carbohydrate intake to an apple and a cup of oatmeal. She also engaged in regular workouts, in order to match the eating habits and exercise regimen of Abby, who runs obsessively and often in place on treadmills and stationary bikes. Both physically and emotionally, says Weigert, her character was starving.

“I stopped feeling very hungry,” she remarks, after adopting this lifestyle. “[The] hunger had been pushed down so far that it didn’t know itself any longer… And it eventually reclaims her, in the way it does to an adolescent. You’re a child, you’re a child, and suddenly, this hunger begins to creep in and creep in and reshapes and redefines you. And this can also happen in mid-life. It’s what happens to this woman.”

The women that Abby sleeps with range in age, but Weigert says there is an “element of mirroring” in each of these scenes. A sexual connection becomes a means of time travel for her character—backward, with an awkward college student concerned with weight loss, and forward, with an older married woman plagued by loneliness.

“Women mirror her. They look just like her,” affirms director and screenwriter Stacie Passon. “There’s a homogeny to her character, and all these other characters are refractions of who she is, so they all sort of add to her character. And I wanted people to see themselves through her as well.”

This is the first feature-length film by Passon, who, like Abby, was jolted into action by the curve of her son’s wayward ball, which hit her in the head. In another mirror between fiction and nonfiction, Passon also lent her residence as the setting for the Abelmans’ divided household. She is also a married mother of two.

Concussion is very much about women. It is “firmly a third-wave feminist film,” asserts Passon, who immersed herself in works by Virginia Woolf, Adrienne Rich, and Camille Paglia during its creation and production. Their influences can be seen in obvious form, as when Abby hands a client a copy of The Second Sex, a major work of feminist philosophy by Simone de Beauvoir. But the touches also creep in with more subtlety.

“In every scene, there was a reinterpretation of some sort of feminist theme,” Passon says.

Although in some respects a fantasy, the film has firm roots in reality, with a strong cognizance of politics and a society that may be changing faster than the LGBT community can keep pace. As New Jersey wrestles with the possibility of marriage equality, Passon is already two steps ahead, portraying a world in which gay people have achieved a model of wedded bliss that, in the world of Concussion, might already be broken. In this respect, Passon says the film is political as well as firmly within the queer canon.

“People ask if it’s a gay film, first of all, because people are like, ‘It’s not a gay film! It’s a universal film.’ But I think that you’re not such a straight audience anymore,” Patton says, responding to past reactions from her viewers. “I think our entire generation was a very inclusive generation. We wanted to bring together people of different colors and races and sexual orientations, but I think we did it to a fault. We consumerized everybody with our inclusiveness. And the thing about gay people, traditionally, is we’re not just like them… And we will redefine marriage in a way.”

Abby’s transgression, says Passon, becomes a way of not only reinventing marriage, but also a means of reclaiming her queer identity.

“I think it was important for me to show that this woman was trying to reclaim her gay self,” the director says. “Something that made her different and interesting to begin with. And she goes. She goes. She goes all the way there.”

Passon was assisted in her first feature film by producer Rose Troche, a veteran of the LGBT film community known for directing groundbreaking works like Go Fish and The Safety of Objects. Troche reiterated this point of the broken model of marriage and the need for the LGBT community to reinvent the form.

Siff and Weigert

“I just thought, having been on the outside for all of these thousands of years, that we would approach marriage in a different way,” Troche says. “It’s like no other contract. If this was you buying a house, and it was this kind of a crappy contract where only 10% of the people lasted… none of us would enter that… But we blindly keep on entering it in this same manner… I was hoping, as a community, we’d say, you know what, I have a different way of doing marriage. I have a different idea of marriage. I’m going to find a new way to make this work.”

“There are a lot of couples, and I don’t care what configuration you are, where [sex] becomes a once a month thing,” Troche says. “And you start to wither a little bit. But the film isn’t just about sexuality. It’s about Abby’s identity. It’s about her wanting to be seen, and be seen in a new way through these women.”

From an outsider’s perspective, Abby Abelman has seamlessly slipped into the model of an upper-middle-class suburban housewife. Her sexual orientation goes unremarked among the straight friends within her social circle. But even there, the rules bend. After remarking that a fellow mother, Sam Bennet, is attractive, a friend chastises her, and reminds Abby that Bennet’s husband “works for Goldman-Sachs,” as if employment with the banking firm were a marker of heterosexuality. Naturally, Abby soon finds herself face-to-face with Bennet at a café where she screens potential clients. She adds her to the list.

“The film takes a look at what on the surface is a pretty conventional marriage – they’re well off, they live in a nice suburban home, they have two kids, she’s a soccer mom – and it looks at this community of these mothers,” says Siff, who also works with Weigert on the series Sons of Anarchy. “What I like about my character is that she’s sort of a stealth bohemian, a stealth iconoclast in the middle of this suburban landscape.”

In spin class or at parties populated with married couples, this community comments with unsettling normalcy on the crumbling relationships of their peers. Abby’s wife, Kate (Julie Fain Lawrence), a divorce attorney who neglects Abby sexually, highlights the extent to which divorce has been accepted as the inevitable result of marriage. In one memorable scene, Kate coolly questions the division of assets after learning another lesbian couple has split.

“How do we stay alive inside of our marriages?” Siff posits. “That’s a question for everybody.”

And what has Passon learned from her experience directing Concussion?

“That I wasn’t so off the mark, and you can reinvent yourself later in life,” she says. “Whether I’m a prostitute or a filmmaker, this was my journey in that way.”

Concussion is out in theaters today.

Like SheWired on Facebook

Follow SheWired on Twitter