The Obituary of Tunde Johnson is a nightmare on repeat. The film's titular character, Tunde Johnson, is a gay Nigerian-American teen forced to relive his death every day. What makes the film particularly jarring are the ways his death manifest: always at the receiving end of police brutality. Tunde writer Stanley Kalu didn't create an inner-city tale of woe—Tunde comes from an upper-middle-class family, lives in the suburbs, and is surrounded by the white gaze. This is to prove that no matter where you grew up or what your education level is, if you're Black, you're susceptible to state-sanctioned violence.

We've seen it come to pass with real-life victims of police brutality like Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Laquan McDonald, Freddie Gray, and countless others. I had the opportunity to sit down with Kalu and lead actor Steven Silver to talk about the experience of making Tunde and how their connection to the material hit close to home.

This story comes from a very personal place for you because of what Black men experience under state-sanctioned violence. Is this what drove you to create The Obituary of Tunde Johnson?

Kalu: I'm from Nigeria and lived in Africa my whole life. I had never in my life been addressed as Black first. Attending USC was a crazy transition of going from the majority to the minority and I found myself being dehumanized systematically—which made me depressed. My appearance is intimidating for some. I’m a tall, large Black man, and in America, people who look like me die too often. But think about the brutality and how much deeper it is for Black queer folk.

Being Black in America and being queer in Africa presents a vicious set of intersectional circumstances—thus making you a target twice.

Kalu: The idea for Tunde hit me all at once, so I really explored the concept in my screenwriting class and wrote [it] when I was 19; it all came together. I submitted my first draft to Sundance and won the competition. I didn’t want to touch it again because writing it was more like a pure expression and an exploration of my feelings about America and about the spaces that I inhabit.

When you read the script, did you know this was something you wanted to be apart of?

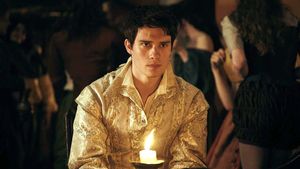

Silver: When I came across this script, I was blown away. Both structurally and emotionally, I’ve never read anything like it, and I knew how important it was to get this made. Also, when I found out a 19-year-old wrote it, that made a bigger impact. To be able to translate an experience that most people endure if they exist outside of the power circle is vital to see on screen.

Tunde is tragic in parts and triggering in others. Was there any point where you had to take a break from the experience. I mean, let’s be real, this hits close to home for so many of us.

Silver: There is a scene where my character gets strangled. I did those stunts with myself and had to do back-to-back takes of myself getting choked. By the time we finished, my throat was sore. I kept myself composed on set, but the moment I closed the door to my trailer, I sobbed for 15 minutes. Even if police brutality doesn’t end in death, that trauma doesn’t go away. Having a glimpse of that intentional physical pain, even in a fictional space, was quite painful in my own psyche.

Kalu: I mean that every black person on set had to leave at one point or another. That scene centered the idea of exactly what's being done to us and we all felt it viscerally because this is happening to real people.

There is this idea that from the moment you’re born, your existence is a political statement and you don’t have a say in that. That brings me to one of the scenes where Tunde is stuck in a situation of white privilege that could get him killed, which is something that’s also happened to me.

Kalu: I realized that being Black in America is to be consistently under the white gaze. The concept of Blackness exists because people were robbed from their homes or brought to a foreign country. And so Blackness is more often than not in conversation with whiteness. When you were born in the system, when you're constantly under a gaze, when you're constantly having to prove that you're one thing and not another, it’s exhausting. We are constantly put in white spaces and have to code-switch. So when I was writing this, I had to put Tunde in those situations—at school, his environment. We are consistently put in spaces where we are uncomfortable or we cannot be our full selves, and scenarios like this are dangerous.

Well, we have to learn how to navigate those spaces, because if we don’t, it could mean even more trouble for us….

Silver: The blind spot here is many people in power assume just because someone is nice to them or treats them well, that’s going to spill over to their minority friends and associates. But then when a Black person or a woman or someone queer steps into their space, they have a different experience.

When you mention blind spot it reminds me of the scene of the confrontation between Soren, the police, and Tunde.

Silver: Soren is going ballistic in that scene! The cops tell him to calm down, but he feels so empowered in that moment that he's not even listening—and that’s because he doesn’t understand the danger he’s putting Tunde in. Even people who consider themselves allies make those mistakes.

With all you have to face in the world, what, who, or where is your personal safe space?

Kalu: Actually never thought about that. I moved around a lot, so finding a particular place is a challenge because I'm constantly not quite fitting in. As for people, I would say my family are my safe space. They live far (it’s a 23-hour flight from California). When I'm with them, I feel completely safe. Outside of that, I do try my best to protect myself, my body, and my mind to make sure it’s safe.

Silver: Until we get to a point where justice is not limited to one group of people, it’s important to make your first safe space your body, or else it’s easy to self-destruct. So for me, I tried to make my safe space so that I don't need to run to a safe space.

The Obituary of Tunde Johnson premiered earlier this month at the Toronto International Film Festival.