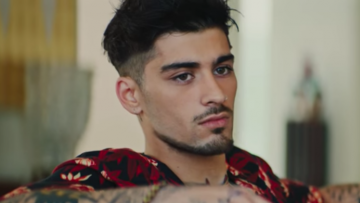

Sara Marcus -- pictured above--author of the new book Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, says the punk ladies of the ’90s changed not only music and style but also sexual boundaries.

“In her kiss, I taste the revolution!”

So goes the ecstatic shriek at the pinnacle of Bikini Kill’s punk girl-power anthem “Rebel Girl.” Released at least three times between 1991 and 1994 — including one version produced by Joan Jett — the track was a fight song for Riot Grrrl, a punk feminist movement of young women that flourished across the United States, and in Canada and the U.K., in the early and mid ’90s.

Riot Grrrl had its roots in the punk scenes of Olympia, Wash., and Washington, D.C. It spread first through the music of all- or mostly female bands based in these two towns, including Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy. (Kathleen Hanna, the lead singer of Bikini Kill, later went on to front the feminist electro-pop band Le Tigre; Heavens to Betsy’s singer-guitarist, Corin Tucker, cofounded the power trio Sleater-Kinney.)

The movement was about far more than music, though. In the early ’90s — a time of Anita Hill and Tailhook, Rush Limbaugh and parental-consent abortion laws — affronts against young women’s dignity seemed endless. Riot Grrrl swiftly crystallized the anger and frustration of a whole generation of young women. Daughters of second-wave feminism, these girls had grown up on promises of equality that seemed to dissolve sometime around adolescence, when the endless opportunities allegedly available to girls in “postfeminist” America began running aground on the realities of constricting gender roles and beauty standards, sexual harassment and assault. These contradictions were enough to make a girl want to scream.

And once Riot Grrrl began, thousands upon thousands of girls did scream, in myriad ways. They picked up electric guitars and drumsticks for the first time. They organized meetings and festivals and conventions. They wrote handmade zines and built underground self-publishing networks to distribute one another’s writing, art, music, and videos.

more on next page...

\\\

(continued)

“Girl love” was one of the movement’s key catchphrases, updating the lauded “sisterhood” of the ’60s and ’70s women’s liberation movement into something more ambiguous. The sisterly bond is utterly desexualized, almost defensively so, but “girl love” leaves things open to interpretation: Is said love romantic or not? When you’re 16, do you ever really know for sure?

Many riot grrrls considered themselves bi, at least in theory if not in practice, which helped the movement sidestep the gay-straight frictions that had riven feminist organizations in the 1970s and ’80s. As Riot Grrrl chapters sprang up in cities and suburbs across the country, each group developed its own unique composition and energy. In Olympia, some lesbians at Evergreen State College considered the Riot Grrrl crowd’s bi-with-a-boyfriend(-and-maybe-a-girlfriend-too) vibe to be too straight for them. In New York, though, the weekly Riot Grrrl meetings and regular concerts, art shows, and festivals acted as a magnet for queer young women.

Although none of Riot Grrrl’s original progenitors identified as lesbians, the movement had taken much of its inspiration from the gay punk networks of the late ’80s and early ’90s. And by 1996, when all the bands originally associated with Riot Grrrl had broken up or were headed that way, the torch was passed to a new wave of specifically queer musicians: all-lesbian supergroup Team Dresch (who frequently toured with Bikini Kill in their early years), power-poppers the Butchies, avant-metal duos the Haggard and the Need.

Crucially, Riot Grrrl was always about resisting definition and defying categorization. In their zines, songs, and artwork, the girls insisted over and over on their right not to have everything figured out. The early and mid ’90s saw a proliferation of “gay-straight alliance” clubs at high schools; but in those organizations that named their members as being either “gay” or “straight,” and in the movements that posited explicit self-disclosure as a necessary basis for (and even as synonymous with) political action, there was little space for a teenage girl who was infuriated by homophobia but still in the process of making sense of her own sexuality — a long, complex process for many people, especially adolescents. Riot Grrrl’s declarations of indeterminacy, its adherents’ refusal to be boiled down to one platform or identity: This is one of the movement’s most important legacies.

Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, published by Harper Perennial, is out now.

Follow SheWired on Twitter!

Follow SheWired on Facebook!

Be SheWired's Friend on MySpace!